Highlights from The Studio Museum in Harlem

One reason we look at art is to see ourselves reflected; I know that place, we say, that light, that joy or pain, that’s part of who I am. It’s reassuring, that affirmation that we’re not alone. Art is also revelation, showing us what we don’t know about ourselves and the lives of others.

Since the murder of George Floyd and the international protests, I’ve been thinking about Black Refractions: Highlights from The Studio Museum in Harlem, a traveling exhibition I saw at the Smith College Museum of Art (SCMA) in Northampton, Massachusetts, this winter, and its power to reflect and provoke reflection, as in “consideration,” as in “light returned from a surface.”

Black Refractions spans a near century of art-making by nearly 100 artists of African descent, with Bill Traylor, born in 1853, at one end of the spectrum and Jordan Casteel, born in 1989, at the other. It has a star-studded lineup: Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Aboud Bey, Mark Bradford, Juliana Huxtable, Jacob Lawrence, Kerry James Marshall, Chris Ofili, Faith Ringgold, Bettye Saar, Lorna Simpson, Mickalene Thomas, Carrie Ann Weems, Kehinde Wiley, Fred Wilson …

… And one international in scope, featuring artists from or working in Africa, China, Europe, the United Kingdom, and the Caribbean as well as the United States.

Previously hosted by The Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco, the Gibbes Museum in Charleston, and the Kalamazoo Institute of Art, it was scheduled to make two more stops after leaving SCMA in April. The show closed early because of the pandemic and is scheduled to open in May 2021 at the Frye Art Museum in Seattle.

Beautiful, inspiring, stimulating, it’s not the kind of show where you kick off your critical faculties and take everything in from the aesthetic equivalent of an overstuffed chair.

With some exhibitions, you can dive deep or drift. That might mean taking a show of Constable’s admittedly superb, revelatory landscapes, for instance, at face value, treating it as a day at the beach, a vacation from your own troubles and what the poet Matthew Arnold called “the turbid ebb and flow of human misery.” It might even deliver a dose of hope that the world is better than it seems, a “land of dreams,” to quote Arnold again.

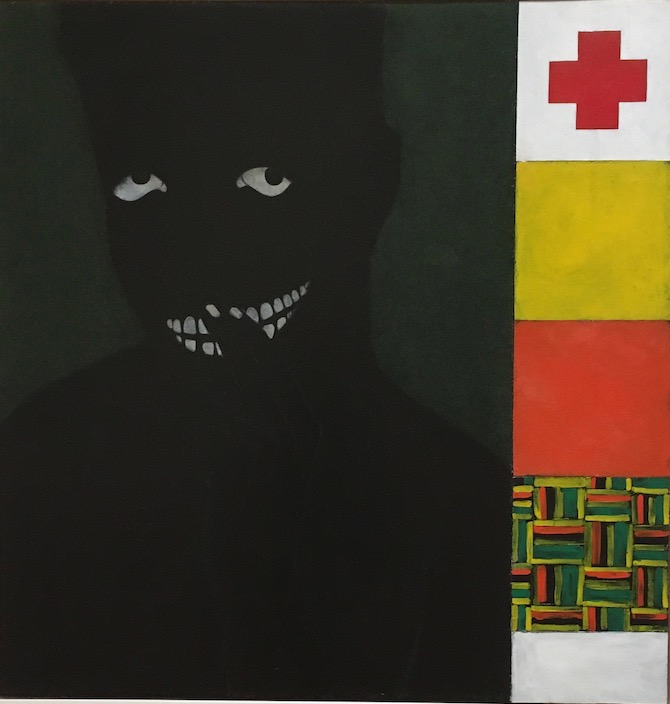

Beauty, nourishment, hope, an escape route to dreamland: All that can be found in Black Refractions, but also sorrow, struggle, pain, and dislocation. It’s not easy being face to face with harsh realities, but more than ever, it feels essential. And because the show presents the sensibilities of so many artists, it also manifests resilience, strength, assertion, courage, resistance, and transcendence.

Purists might argue that art should be viewed and have an impact without the viewer knowing the artist’s life story. I’m not a purist. I was moved by the stories of people who, against seemingly overwhelming odds, made extraordinary art, Clementine Hunter and Bill Traylor, for example. I wanted to know more about Elizabeth Catlett, James VanDerZee, and others (See the brief bios and links to more information at the end of this post.) I’m not immune to star power, either, as exemplified by 33-year-old Juliana Huxtable, who already has exhibited at MoMA, New Museum, and the Whitney.

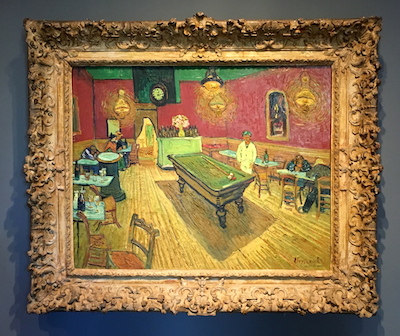

Anyone who skipped reading the wall labels would still feel the strong narrative pull of, among others, River, Maren Hassinger’s snaking sculpture of chain and rope, Mickalene Thomas’s rhinestone-encrusted Panthera, and Kehinde Wiley’s Conspicuous Fraud Series #1 (Eminence), a portrait of a man standing amid the floating clouds of his hair.

These and other works can be seen as investigations into history, stereotypes, and social constructs and values but also into the natural world, the nature of painting, and the nature of portraiture.

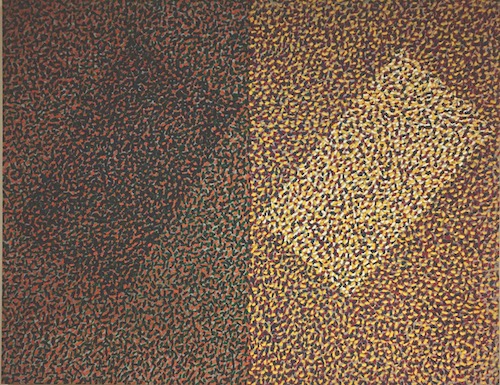

In other works, formal considerations seem to be what interested the artist, but that generalization may or may not hold when you take a closer look.

If there is a generalization to be made about Black Refractions, (and I know I’ve made some and will make a few more before I’m through), it might be that generalizations don’t do it justice. Quite the contrary, in fact. Take the idea of “black art,” for instance.

In the exhibition catalog, Studio Museum Director Thelma Golden states, “For me, to approach a conversation about ‘black art’ ultimately meant embracing and rejecting the notion of such a thing at the very same time.”

So many of the artists represented in the show have come up against institutionalized ideas about what Art is and who can make it.

A related question: What should art do? To paraphrase Bertolt Brecht, should it be a mirror held up to reality or a hammer to shape it? (Brecht came down on the side of “hammer.”)

The Studio Museum in Harlem started out as a hammer, or maybe an artist’s mallet, an instrument to carve a new vision out of obdurate materials. As Columbia art history professor Dr. Kellie Jones explains in the catalog, the museum was founded as “a place to support artists of the African diaspora, who, throughout history had been largely shut out of exhibition and commercial opportunities … during a time of unbridled protest in the world of culture.”

That would be 1968, a time fraught with protest. The civil rights, antiwar, women’s, and environmental movements were all taking to the streets. Activism and advocacy, a desire to alter present reality and rewrite art history, have shaped The Studio Museum’s development over the past 50 years.

The museum wasn’t conceived as a repository of art, but it now has more than 2,500 works in its collection, reflections of myriad perceptions of reality, social, political, personal: Art as a hammer and a mirror.

Besides the imagination, complexity, and nuance evinced by the works in Black Refractions, there is wit. Wry, ironic, sometimes sardonic, it denotes the disconnect between an individual’s dead-on perceptions of reality and society’s assertions of what is.

The primary definition of refraction is the phenomenon of a ray of light being deflected from a straight path as it moves from one medium into another. It’s diversion; it’s distortion. It’s also what makes a mirage and a rainbow.

This show presents creativity refracted: passing through painting, sculpture, photography, video or another art form, informed by intellectual inquiry, honed by artistic rigor, sometimes forced by the artists’ experiences in the world to take a harder, longer path but not broken. Given form, substance, life.

This post is my attempt to convey my appreciation of the exhibition and show a sampling of the art in it. For those who want to know more about it, the museum website is a great resource and so is the exhibition catalog. The museum itself is closed but has online offerings.

Clementine Hunter (1886-87-1988), the granddaughter of an enslaved woman, began painting in her fifties, using supplies left behind by a guest of her wealthy employer, and went on painting for nearly another 50 years, on whatever material she could find: paper, roof shingles, window shades.

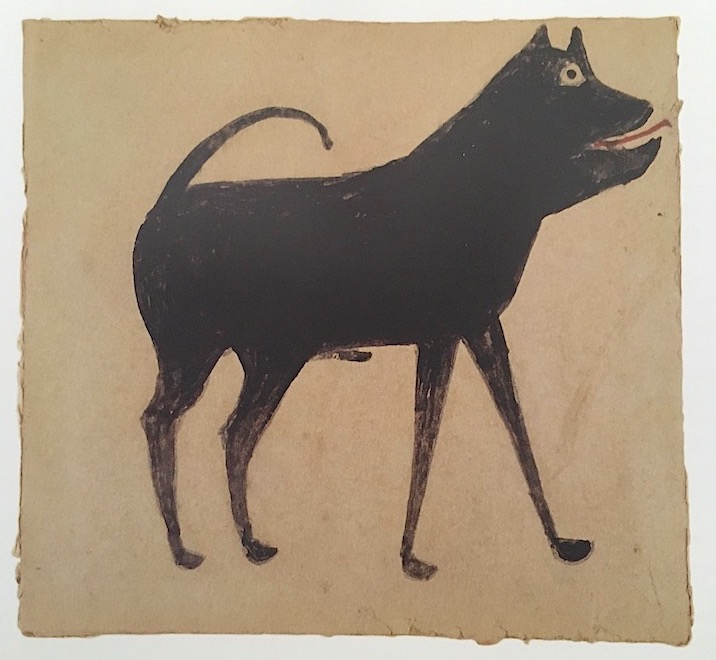

Born into slavery and a sharecropper most of his life, rendered jobless and homeless by crippling rheumatism in his seventies, Bill Traylor started making art in his late eighties, when he was sleeping nights in the backroom of a funeral home in Montgomery, Alabama. He made more than a thousand drawings and paintings using materials he found or was given.

Elizabeth Catlett merged activism with art-making. Born in Washington in 1915, she was denied admission to Carnegie Institute of Technology after the school learned she was “colored.” She went on to study with Grant Wood and Ossip Zadkine, made stylized, sensuous sculptures, such as Mother and Child, designed posters for Malcolm X and Angela Davis. In 1959, the State Department declared her an “undesirable alien” because of her leftist politics (she was living in Mexico at the time) and denied her a visa to return to the United States throughout the following decade.

The photographs of James VanDerZee (1886-1983) captured many of the leading lights of the Harlem Renaissance, as well as middle-class blacks and street scenes—the essence of a time and place. The arc of his career was wide, too: in 1925, he did the portrait of the Midnight Ramblers. A year before his death, he photographed artist Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Nonetheless,

Nonetheless,

After accumulating these bits and pieces, I still felt I was just skirting the edges of his personality. My search reminded me how difficult it is to know anyone’s motivations, much less those of somebody dead for nearly three quarters of a century. Then I looked once again at photographs of the Mill River flood and had a flash of insight.

After accumulating these bits and pieces, I still felt I was just skirting the edges of his personality. My search reminded me how difficult it is to know anyone’s motivations, much less those of somebody dead for nearly three quarters of a century. Then I looked once again at photographs of the Mill River flood and had a flash of insight.

But there’s drama among the chorus, something doughty and stout-hearted about even the smallest specimens. I’m always touched by the appearance of the first snowdrops in my garden.

But there’s drama among the chorus, something doughty and stout-hearted about even the smallest specimens. I’m always touched by the appearance of the first snowdrops in my garden.

To the right of the Gallery lobby is the 1928 neo-Gothic Old Yale Art Gallery, designed by a member of the Class of 1891,

To the right of the Gallery lobby is the 1928 neo-Gothic Old Yale Art Gallery, designed by a member of the Class of 1891,

From a distance, his immense “Society Woman’s Cloth (Gold)” shimmers with the radiance of precious metals. Up close, you see it’s an illusion—or is it?—the “cloth of gold” is painstakingly fabricated from thousands of aluminum liquor bottle caps linked by copper wire.

From a distance, his immense “Society Woman’s Cloth (Gold)” shimmers with the radiance of precious metals. Up close, you see it’s an illusion—or is it?—the “cloth of gold” is painstakingly fabricated from thousands of aluminum liquor bottle caps linked by copper wire.

You must be logged in to post a comment.