Visiting Dartmouth College’s art museum in Hanover, New Hampshire.

A leaping, frilly Hiroshige wave on an expansive felt panel looms before you as you enter the two-story atrium of the Hood Museum. Reopened last January after three years of renovation and expansion, the Hood makes a strong first impression, with lofty spaces and subtle effects. I was impressed by the textures and attention to detail: glazed bricks with a porcelain sheen, satiny concrete walls, burnt-orange piping along the edge of a tweedy charcoal-gray carpet.

The Hood can be proud of its collection, 65,000 works of art from all over the world and across millennia, but rather than being simply a rich repository, it focuses first and foremost on its role as a teaching museum.

The highly regarded firm Tod Williams Billy Tsien Architects reconceptualized the original museum, by noted postmodern architect Charles Moore, which opened in 1985. Among the major changes Williams and Tsien made were to add five galleries and three classrooms and create a new entrance and the atrium.

According to the firm’s website, they sought to bolster the Hood’s teaching capabilities and “encourage a sense of curiosity by as much direct contact as possible.” I didn’t know the Moore building, but the new Hood is an airy, lucid structure. The galleries’ dimensions are gracious, and the lighting is excellent, with natural light introduced as much as possible.

Nonetheless, at some point, my excitement about being there began to fade. As I wandered, I wondered: Can a museum be too perfect?

Nonetheless, at some point, my excitement about being there began to fade. As I wandered, I wondered: Can a museum be too perfect?

My first bump in the road came down a hall on the ground floor, when I spotted Mara Superior’s “Angelo Da Vendemmia—Castle Vase.” I was thrilled to see something in a museum by someone I know (at least to say hello to). An unforgiving medium, porcelain in Superior’s hands and sensibility becomes a witty, lyrical vehicle of expression, and this was a finely wrought piece of decorative art.

Maybe it was the sight of the angel looking out with downcast wings, hands meekly folded in front of her. Maybe it was the vessel’s tucked-in-a-corner location, or the fact that it was sealed in a glass box… but, not for the first time in my museum-going, I felt a sense of dislocation. Not mine, the objects’. Seeing a Navajo rug high on a white wall, silver serving spoons supine within a vitrine, African ceremonial masks untouchable on rigid stands, I’m struck by how removed they are from their original homes, context, life.

Would their makers be dismayed or gratified to see them in these neutral spaces?

It’s not possible, I know, for the vase to be filled with bachelor buttons, poppies, and Queen Anne’s lace and displayed on a scrubbed wooden table by a sunny window. Any museum would exhibit it as the Hood does. Still, my heart went out to it, and my mood clouded up a little, à la the overcast October sky outside.

As I went on, the restrained design of this newly recast museum was having an untoward effect on me. Was the setting too understated, too neutral? Were the surfaces too bland, was there too much white space? Instead of clearing the way for an energetic exploration, the cool atmosphere seemed to tamp down my enthusiasm, and the art’s vitality.

Seeking an antidote, I homed in on the many spectacular works on exhibit, such as the gorgeous Assyrian reliefs. Showcased on the ground floor, the massive slabs originally decorated the palace of a monstrous king, Ashurnasirpal II. They are a fascinating study in contrasts: larger-than-life scale/fine work, ancientness/realism. Wings/sandals.

In one, a divine bodyguard of sorts stands behind the king, a bracelet on his wrist (I had to resist reading it as a Swatch) and a pail in his hand. I was struck by how the anonymous artists from the ninth century BCE emphasized the arm, leg, and hand muscles and in so doing, conveyed the might of this genie, and the king and his empire.

In the Melanesian gallery, I met a crowd of personalities. Elaborate carving distinguished some objects; many of the suspension hooks, for instance, which served as both talismans and as a means of securing food and other valuables. Others, such as the fish (bottom row), were stylized, wonderfully simple. Whether there was a wealth of detail or the merest suggestion, the objects had mojo.

“Global Contemporary: A Focus on Africa,” an exhibition up through December 1, includes large-scale works that dominate the gallery they are in. My favorite was a dazzling textile sculpture by El Anatsui, an artist whose work I’d first seen at the Yale University Art Gallery. A massive piece (20 by 18 feet), “Hovor” had the awe-inspiring effect of the Assyrian reliefs. El Anatsui achieves a kind of alchemy, art conjured from aluminum bottle tops and copper wire. The title, derived from the Ewe words ho and vor, can be translated as “valuable cloth.”

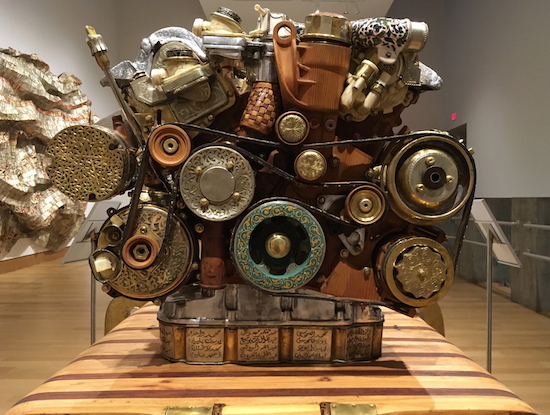

In conversation with “Hovor” were the elegant, fantastical engine “V12 Laraki” by Eric Hove and Elias Sime’s “Tightrope: Infatuation,” in which castoff circuit boards have been combined to suggest an intricate aerial view of a city.

I gravitated to a variety of paintings that had in common color and energy.

In the gallery dedicated to Australian aboriginal art, the vivid orange tones and complex patterns of George Tjungurrayi’s “Karrukwarra,” left, and Naata Nungurrayi’s “Marapinti” heated up the room (both photos are details).

Toward the end of my visit, I saw the meteorological mood had lifted. The clouds had broken up; sunlight was breaking through. The dramatic window wall that forms part of the Hood’s facade framed a classic New England vista: a town green, a spectrum of fall foliage, a sharp blue sky.

My own frame of mind had improved. Good intentions are not always enough when it comes to fruitfully spending time in a museum. Sometimes it all clicks, other times, not so much. That’s not necessarily the fault of the place. Is the Hood too perfect? Maybe. Maybe on another day, I’d have been more receptive to its atmosphere.

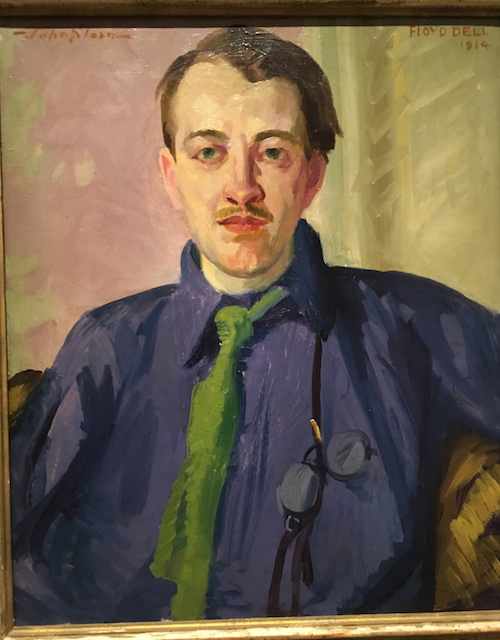

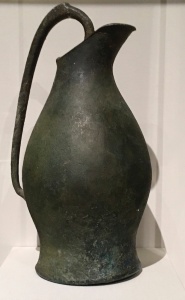

And since my visit, it’s dawned on me how terrific it is that in a small town in the wilds of northern New England, there’s a museum where you can see a 2,000-year-old Celtic bronze pitcher and a sculpture by Yayoi Kusama—for free, no less.

In any case, I would be a sorry thing if I weren’t touched by the many outstanding artworks I saw and—here’s the happy ending—the best came last.

Call me sentimental, I found Paul Sample‘s “The Return” really moving, with its powerful sense of place, its narrative strength, and its warmth of feeling.

Right down the center of the painting, a young G.I., duffle on his shoulder, makes his way along a slippery road. His khaki uniform is at one with the dun tones of the palette. He’s the only living thing on the scene; the only other sign of life is a puff of smoke from a train in the background. Most likely, the town portrayed is in New Hampshire or Vermont; Sample was a Dartmouth grad and taught art there for many years.

“The Return” represents a deeply emotional and personal experience. Soldiers and sailors went through years of combat en masse, but after demobilization, the last leg of the journey for many of them was making their solitary way back to a small town. There was no band playing at the train station, maybe not even a dog barking. This soldier just puts one foot in front of the other, much as he had done on the march; I hope he found a warm welcome waiting for him when he got to where he was going.

Tell me, what is the perfect museum in your eyes?

And to read more about the Hood’s expansion and mission, click here.

Good to see your two contrasting New England scenes–your sunny, crackling photo and the quiet cold “Return.”

LikeLike

Thanks so much! A weather theme, I realized, snuck into this post.

LikeLike